The recent acquisition of X-ray images of canines from adult individuals of Vetricella has allowed us to perform the determination of age at death by the canine radiographic method (Cameriere et al., 2007a,b; 2009). Traditional anthropological methods to estimate age at death of adults can be based on observations of remodelling and skeletal degeneration, such as cranial sutures closure, sternal ends of the ribs, remodeling of the pubic symphysis and of the auricular surface of the ilium, dental wear and others.

Many of these methods have been revised and improved over the years, but they tend to produce wide age intervals even in the case of well-preserved skeletons. Identification of older individuals is particularly problematic and individuals over 50 years of age seem to be underrepresented in skeletal samples.

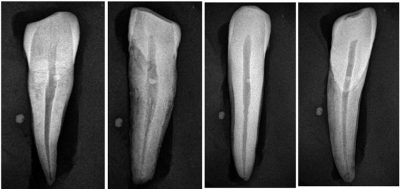

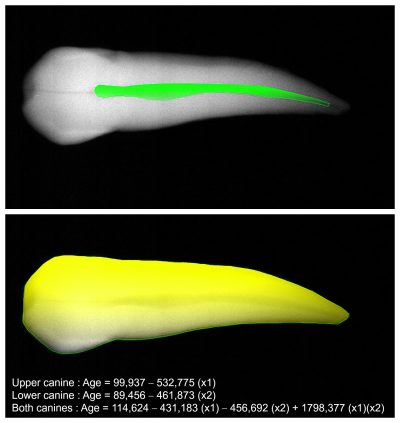

Cameriere’s method, is based on production of secondary dentine filling pulp chambers in dental roots is a regular, continuous process occurring in adult individuals, and it can only be modified by caries or advanced wear. This radiological method estimates individual age by tooth/pulp ratio in canines. Digital X-rays, saved as high resolution images (Fig.1), are processed to obtain the areas of both tooth and pulp chamber (Fig.2-3). Age was estimated by two of the linear regression equations proposed by Cameriere et al. (2009) for the pulp area/tooth area ratios of upper and lower canine.

The advantages of this method can be summarized in some fundamental points: the method is non-destructive; it uses a particularly resistant anatomical part , the canine, therefore allows the determination of the age in many more individuals within a sample, as already demonstrated in other studies (De Luca et al, 2010); the progressive transformations of the tooth/pulp ratio are not affected by individual, social or population variables; lower standard error of estimation, than commonly used anthropological methods for age estimation; finally, it is very accurate even in older overcoming the problem of underrepresentation of individuals over 50 years of age in skeletal samples.

Moreover, the method was tested with excellent results on contemporary and archaeological samples (Cameriere et al., 2006; De Luca et al., 2010; 2011; Jeevan et al., 2011; Fabbri et al., 2015; Viva, 2017) and recently verified on dental sections of individuals of known age (D’Ortenzio et al., 2018).

In our specific case, this methodology has provided age estimations, with lower error, highly superposable with traditional anthropological methods, in fact confirming in most cases our previous analyses. In two cases, age estimations by anthropological methods was unclear due to pathological states of individuals and the use of the radiographic method was fundamental. Finally, we estimated a greater variety of ages of old individuals, generically defined as “50+ old adults”, among which there was a 65-year-old, a important fact for delineating more realistic mortality profiles.